An extract from The Wonders of Waqf, which is a translation of selected chapters from Min Rawāʾiʿ Ḥaḍāratinā by Dr Muṣṭafā as-Sibāʿī

|

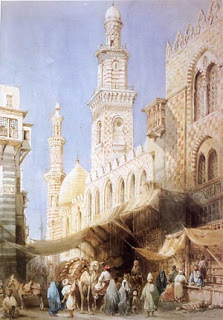

| The

Bimaristan of Qalāwūn, Cairo |

One of the principles that our civilisation is based on is combining between the needs of the body and the needs of the spirit. Taking care of the body and its demands is considered necessary for realising man’s happiness and illuminating his spirit, and one of the transmitted statements that laid down this foundation of the Messenger of Allah’s civilisation, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, is his words: {Indeed your body has a right over you.}[1]

What is noticed from the Islamic acts of worship is the realisation of the most important objective of medicine, which is the preservation of health,[2] and thus prayer, fasting and Ḥajj and what they entail by way of conditions, pillars and actions all preserve the health of the body along with its energy and strength. If we add Islam’s struggle against diseases and their proliferation and its desire to seek treatment that combats them, you will know what strong foundations our civilisation built in the field of medicine and the extent to which the world benefitted from our civilisation in establishing clinics and medical institutions, producing doctors whose contributions to science, and to medicine in particular, are still boasted about by humanity.

The Arabs knew about the medical school of Gondishapur,[3] which was founded by Khosrau in the middle of the sixth century CE and some of their doctors graduated from there, such as al-Ḥārith ibn Kaladah, who lived in the time of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace. He would advise his Companions to seek treatment from him whenever they were afflicted with illness. In the age of al-Walīd ibn ʿAbdul Malik, the first hospital in Islam was founded, and it was exclusively for lepers. Physicians were appointed and provided for and the lepers were provided for and quarantined, as well as the blind. Then the establishment of clinics followed and they were known as bīmārsitānāt, i.e. houses for the sick.

The hospitals were of two types; stationary and mobile.[4] As for the mobile, it was first known in Islam in the time of the Prophet, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, in the Battle of the Trench, as there was a tent for the wounded. When Saʿd ibn Muʿādh was wounded in his medial arm vein, he, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, said, ‘Put him in Rufaydah’s[5] tent so I can visit him from near.’ It was the first mobile military hospital in Islam and then the caliphs and kings who came after expanded it, such that the mobile hospital came to be equipped with everything that the patients needed, including medical treatment, food, drink, clothes, physicians and pharmaceuticals. It would move from town to town in areas where there was no stationary hospital. The minister ʿĪsā ibn ʿAlī al-Jarrāḥ wrote to Sinān ibn Thābit, who was in charge of the hospitals in Baghdad and elsewhere, ‘I’ve been thinking about the people who live in the rural areas of Iraq[6] and how none of those towns are free of sick people and yet there are no physicians to treat them because there are no physicians in the rural areas. Therefore, there should be a delegation of physicians with containers of medicines and syrups and they should travel around the rural areas and stay in each locality for as long as necessary, giving treatment to the people there. Then they can move on to the next locality.’ In the days of Sultan Maḥmūd al-Saljūkī, one of the mobile hospitals was so big that it had to be carried by forty camels.

As for the stationary hospitals, they were many in number and spread throughout the cities and capitals, and every small town in the Islamic world, at that time, had at least one hospital. Cordoba alone had fifty hospitals.

The hospitals were of different kinds. There were hospitals for the army that were run by specialist physicians, in addition to the caliph’s physicians and those of the commanders and leaders. There were hospitals for prisoners and every day physicians would go around and treat the sick with the necessary medicines. One of the things the minister ʿĪsā ibn ʿAlī al-Jarrāḥ wrote to Sinān ibn Thābit, the head of the physicians in Baghdad, was, ‘I have been thinking about those who are in prison. Due to their great number and the aridness of where they are, it is inevitable that diseases will afflict them. Therefore, they should have their own physicians who visit them every day and provide them with medicines and syrups, and they should go around the prisons and treat those who are sick.’

There were emergency stations that were close to the grand masjids and public places where the masses would congregate. Al-Maqrīzī tells us that when Ibn Ṭūlūn built his famous grand masjid in Cairo there was a place for ablution[7] and a pharmacy at the back that contained all the medicines and syrups. There were also servants and a physician who would sit every Friday and treat any worshippers who were afflicted with illnesses.

There were general hospitals, which opened their doors to treat the masses. They were divided into two separate departments; one for males and one for females. Each department had numerous halls and each hall was for a specific illness. There were those for internal illnesses, illnesses of the eye, wounds, broken bones and orthopaedics, as well as mental illnesses. The department for internal illnesses was also divided into rooms, and thus there were rooms for fevers, rooms for diarrhoea, and so forth. Each department was run by a chief physician, and thus there was a chief physician for internal illnesses, a chief physician for wounds and orthopaedics, a chief physician for illnesses of the eye, and so forth, and all the departments had a general chief physician called a sāʿūr, and it was the name given to the head of the physicians in a hospital. The physicians worked in shifts and each physician had a specific time during which he would remain in the hall that he treated patients in. In each hospital there were a number of servants, assistants and nurses, both men and women, and they had ample, fixed salaries. In each hospital, there was a pharmacy that was known as a khizānat al-sharāb and it had various kinds of syrups and precious creams as well as excellent preserves, different medicines and superior perfumes that could not be found anywhere else. There were surgical instruments, glass vessels, bowls and other items the like of which would only be found in the storehouses of kings.

The hospitals were also medical institutions, for in each hospital there was a large lecture hall in which the senior most physicians would sit with other physicians and the students, and next to them were instruments and books. The students would sit in front of their teacher after examining the patients and finishing their treatment. Then there would be talks and discussions about medicine between the professor and his students and they would read from medical textbooks. Oftentimes, the professor would have the students accompany him inside the hospital for practical lessons, in which he would treat patients with them being present, as happens today in hospitals that are attached to medical colleges. Ibn Abī Uṣaybah, who studied medicine in the Nūr al-Dīn Bimaristan in Damascus, said, ‘After al-Ḥakīm[8] Muhadhdhib al-Dīn and al-Ḥakīm ʿImrān had finished treating the patients who were staying in the Bimaristan, and I was with them, I sat with Sheikh Raḍī al-Dīn al-Raḥbī and watched how he obtained information about illnesses, made the overall diagnoses of the patients and wrote out prescriptions, and with him I researched into many illnesses and treatments.’

A physician would not be allowed to treat by himself until he had completed an exam in front of the senior most physician of the state. He would present a thesis to him in the specialty that he wanted to get a license in, and it would be something that he had written himself or something that a major scholar of medicine had written and to which he had added his own studies and commentaries. He would thus be examined on that and asked about everything that was connected to that discipline. If he answered the questions properly, the senior most physician would grant him a license that allowed him to practice the medical profession. It came to pass in the year 319 AH (931 CE), in the days of the caliph al-Muqtadir, that one of the physicians made a mistake in treating a man and he died. The caliph thus ordered that all the doctors in Baghdad be re-examined, and they were examined by Sinān ibn Thābit, the senior most of the physicians in Baghdad. Their number in Baghdad alone reached over eight hundred and sixty, and this does not include the famous physicians who were not re-examined and the physicians who worked for the caliph, the ministers and the rulers.

We must not fail to mention that each hospital had a library attached to it that was filled with books on medicine and other subjects that physicians and their students need, so much so that it was said that in the hospital of Ibn Ṭūlūn in Cairo there was a library consisting of more than 100,000 volumes in all the sciences.

As for the process of being admitted into the hospitals, they were free of charge for everyone. There was no difference between the rich and the poor, the near and the far, the noble and the unknown. First of all, the patients were examined in the outer hall. Those who only had a mild illness were prescribed treatment and then they went to the hospital’s pharmacy. Those whose illness required that they be admitted to the hospital had their name registered and then they entered the bath house. Their clothes were removed and they were put in a special waiting room. Then they were given hospital clothes and entered into the hall that was specifically for people suffering from the same illness. Each patient was given his own furnished bed with good furnishings. Then he was given the medicine that the physician has designated for him and the right foods for his health[9] in the necessary portions. The patient’s food consisted of meat from sheep, cows, birds and chicken, and the sign of being cured was the patient’s ability to eat a whole loaf of bread and a whole chicken in one meal. If the patient had entered the recovery phase he was transferred to the hall for convalescents. When he had completely recovered, he was given a new suit of clothes and a sum of money to compensate for the time that he had been unable to work. The hospital’s rooms were clean with water flowing through them and its halls were furnished with the best furnishings. Each hospital had inspectors who checked for cleanliness and observers who looked over financial records, and oftentimes the caliph or ruler would visit the patients himself and make sure they were being treated well.

This

is the system that was prevalent in all the hospitals that were established in

the Islamic world, in the west as in the east…in the hospitals of Baghdad,

Damascus, Cairo, Jerusalem, Makkah, Madīnah, the Maghreb, Andalusia…and we

shall confine ourselves to discussing four hospitals in four capital cities of

Islam in those times...

[1] Related by al-Bukhārī and Muslim.

[2] ʿAlī ibn ʿAbbās defined medicine as a science that looks to preserve health for the healthy and restore it to those who are sick.

[3] (tn): in modern-day Iran.

[4] (tn): known as field hospitals nowadays.

[5] (tn): i.e. Rufaydah al-Aslamiyyah, who is recognised as the first female nurse in Islam.

[6] Ar. as-sawād.

[7] Ar. mīḍāʾ.

[8] (tn): this word also means ‘physician’ and is used as a title in this context.

[9] (tn): This is an aspect that appears to be completely ignored in Western conventional medicine. For example, a patient suffering from pneumonia will be served ice-cold water, which could prove deadly, while the necessary warming foods, such as turmeric or cayenne pepper, will never be offered. It is also normal to see patients in Western hospitals eating various kinds of junk food, especially those that are high in sugar, high fructose corn syrup, aspartame and MSG. The connection between health and diet, or treatment and diet, is never considered.

No comments:

Post a Comment